Author: deniz

Kneeling Sculpture

All of the Sheep

All of the Sheep, wool, 280 cm x 200 cm (2025)

All of the Sheep is a handwoven weaving hanging in the environmental agency’s new office headquarters in Odense, Denmark.

The weaving is made from wool sourced in Turkey and Denmark. Just as the artist himself is shaped by multiple cultures, the weaving is composed of wool from different origins.

In the process of creation, the full spectrum of materials from wool production has been used – from the cleaned, white, and processed wool to the raw, untreated fibers close to the sheep’s skin, unbleached by the sun and therefore golden. Even the neon-colored markings used to identify the sheep have been integrated into the work. Nothing has been discarded; materials that would normally be disposed of has been given a place in the weaving. Hence the title: All of the Sheep.

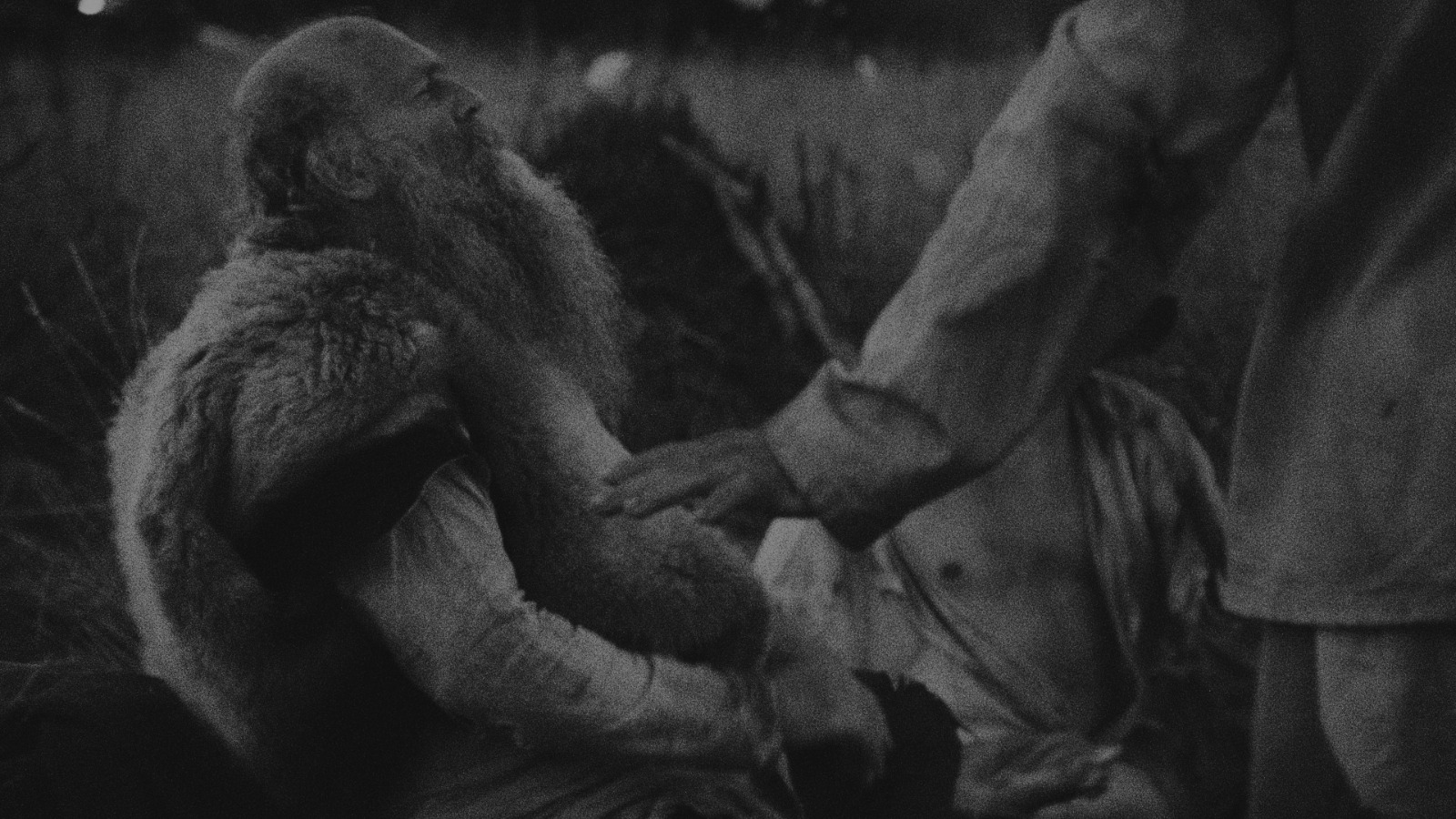

Hunter, Gatherer

Hunter, Gatherer (2025), cinemascope, 29 minutes

A Turkish man is travelling around the Balkans to make a PhD application film about the architecture of psychiatric hospitals.

As his journey progresses his ambitions drive him to change the film and he begins to film the patients he encounters. Once the relatives of a patient discover he’s been filmed, dire consequences are set into motion for the filmmaker.

Produced with The Dutch Film Foundation and the Mondriaan Foundation

Italian House

16 mm (2023), 5 minutes

The Shipwrecked Triptych

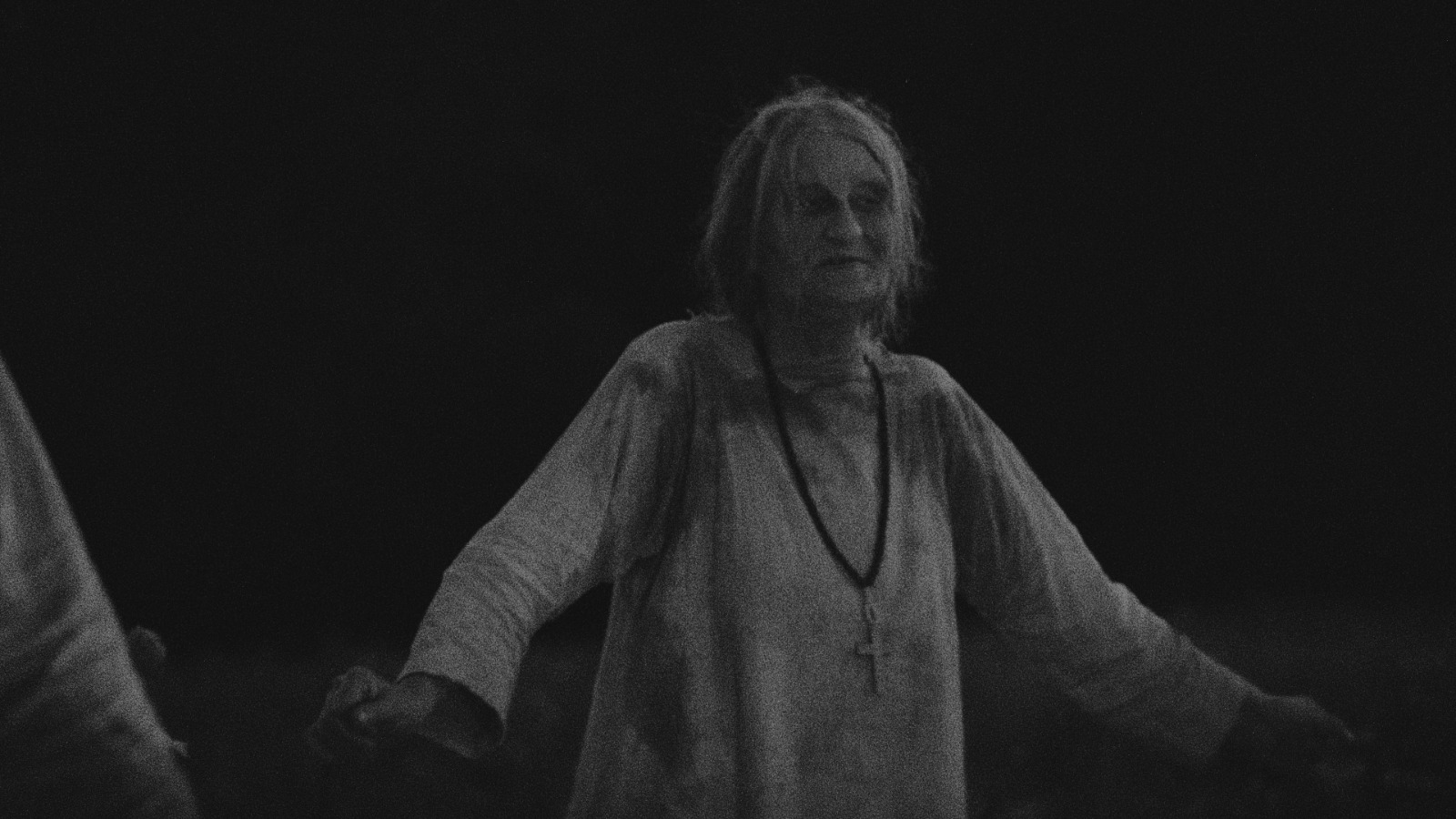

The Shipwrecked Triptych Part I: Mutiny

2023, 16 mm kodachrome, duration: 30 minutes

New Years Eve 1982 in an elderly home in Germany. The nurses decide to put the inhabitants to sleep early to have a party.

The Shipwrecked Triptych Part II: Boarding

2023, 35 mm transferred to VHS, duration: 30 minutes

A bureaucrat turns up unexpectedly to inspect a Congolese family on a hot summer’s day in Western Germany in the late 1980’s. As he stays around after it gets dark, the parents begin to expect that something isn’t right.

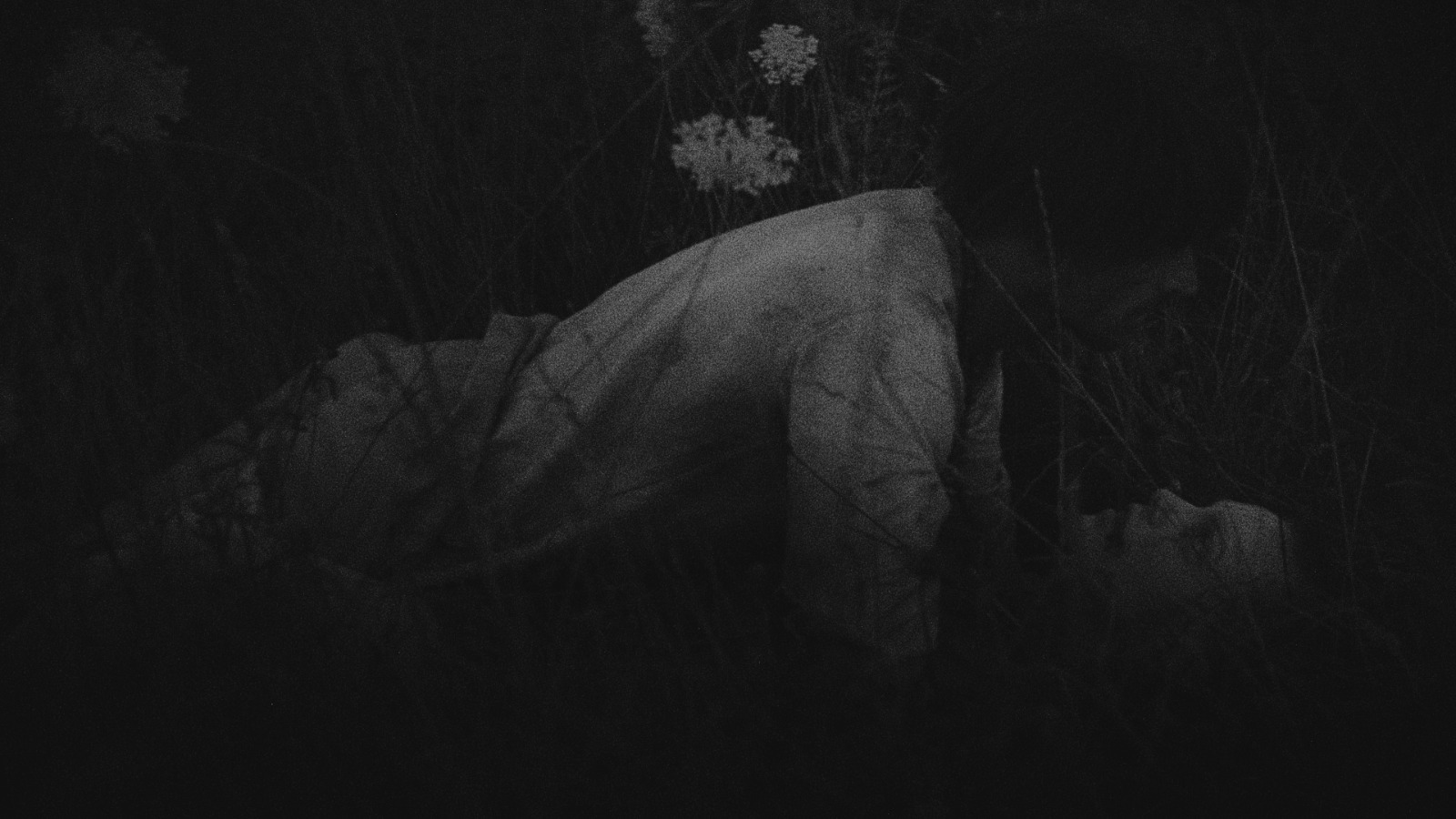

The Shipwrecked Triptych Part III: Adrift

2024, 16 mm b&w kodachrome, duration: 30 minutes

A ship of fools roams around the German countryside anno 1505. One of them is cast out of the group and has to survive by himself.

A Piece of Work

2023, b&w, duration: 30 minutes

A Piece of Work is a twin work to A Vacation. A revisit, additional thoughts, as it were, which describe the conspicuous conditions under which the first film was made. The title has three meanings: it denotes an art work. In a colloquial sense, it refers to a “difficult individual”. Lastly it represents a contrast to the title A Vacation. In this film, which can be described as equal parts comedy, sociological study and self-criticism (a Western artist inserting himself in a context he is not fully at home in), Eroglu places himself in front of the camera as an actor alongside his father and the actor of A Vacation Hüseyin Isçi besides casting a roster of locals from the first film. In contrast to A Vacation, which was shot in cinemascope to convey the vistas of the mountainous location, this film is shot in the square aspect ratio 4:3, and focuses more on the collective of people that populate the film as it describes the laborious efforts it took to produce the first film. One film portrays this place in colour, the other is shot in b&w. Its focus is the interiority of the place and the people, whereas A Vacation is characterised by an exteriority, panoramas and figures in those landscapes that serve as a metaphor for agency: the idea that moving freely in a landscape can signify agency in an oppressive environment. Here, instead of open fields and emancipation, we are locked inside deterministic squabbles. Each character assuming their role; the ambitious artist, the apathetic actor, and impatient baba.

The film critically probes the concept of the “political artist”, who, through an activistic act, seeks to enforce change.

Blut und Boden

2019, duration: 10:05 minutes

The title refers to the nationalist slogan of “blood and soil”; a racist ideal of a national body united with a settlement area.

‘The Brown Study’ by Deniz Eroglu

Interview with Juliane Duft for KubaParis (August 2019)

Mutlu

Porcelain, 89 cm x 45 cm, (2019)

From the catalogue of “Flashing and Flashing!” at MAXXI museum:

Mutlu (“happy” in Turkish) is a so-called Turkish toilet displayed as a sculpture on a pedestal. On the surface a title is provided, a reference to the “R. Mutt” signature of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain. Filth, annoyance and discomfort – the characteristics that the collective imagination associates with a urinal – are transitively thrust at this nationality, giving the lavatory its name. When installed on the ground, the artwork represents an unexpected obstacle, a metaphorical image of how, in Europe, Middle Eastern immigrants are increasingly seen as an unwelcome presence.

Trick or Treat

Mixed media, (2019)

Trick or Treat is a conceptual mise-en-scene of a candy store where six custom made candies are offered to the public.

Excerpt from the exhibition text:

Eroglu employs curatorial decisions as well as artistic imagination to create a sensorial experience through the symbiosis of thoughts and flavours. By merging taste and visual components, he has developed a “language of sweets” that formulates questions of an abstract and critical sort. Trick or Treat is an ambiguous entanglement of writing, curating and various gastronomical endeavours.

“Freedom of Movement” Stedelijk Museum Online Catalogue (25th of November 2018 – 17th of March 2019)

Exhibition catalogue for “Witness” at Brandts Museum (31st of August 2018 – 21st of January 2019)

We go round and round

Ceramics and polyester

Dimensions: 46 cm x 18 cm x 18 cm (2018)

A Vacation

Running time: 29 minutes, (2018)

The arrival of a solitary stranger to a remote area in the Turkish highlands slowly upsets the unspoken social structure of the local community, as there is more to this man than his modest appearance might disclose at first sight. As strange events begin to unfold, the locals become increasingly suspicious to the outsider. Operating within a cinematic fiction of its own enigmatic design, ‘A Vacation’ immerses us in a specific yet elusive world where the silent and misty landscapes turn into the site of an equally silent violence and repression. With its evocative imagery and dark-scented ambience, Eroglu’s elliptic narrative offers an analysis of the illusion of freedom and the mechanics of repression at a time when these sort of reflections can be applied all too well to what is happening in the world around us.

From the Sharjah Film Platform catalogue:

“In this collaboration between Deniz Eroglu and Hüseyin Isçi, the artist attempts to convey Isçi’s current existential conditions. The film examines the six-month imprisonment of the actor on suspicion of supporting the 2016 coup d’etat in Turkey and his fear of being indicted.”

Actors: Hüseyin İşçi, Beytullah Korkmaz, Olcan Çakmak, Kahraman Karasan, Mahmoud Karataş

Produced by Mustafa Eroglu & Cem Eroglu

Cinematographer: Nicolas Geissler

Sound design: David Loscher

Witness (Şahit)

4-channel video installation

Running time: 4 x 15 minutes

Aspect ratio: 16:9

(2018)

Commissioned by Brandts Museum

Witness (Şahit) is a video-installation that consists of four films that were recorded in different regions across Germany.

In it the artist shows to us the living conditions of four protagonists (two Turks, an Armenian and a Kurd) who share their profession, that of a kebab worker, but aside from that lead very different lives.

The work takes its inspiration from the case of the NSU-murders, in which two neo-Nazis drove around Germany over the span of six years, and in a way that appears arbitrary, assassinated nine different people, mostly immigrants working as kebab workers or green grocers.

The resulting tapestry of personal stories involves more than 30 actors, and as the spectator immerses herself in it, connections and parallels will become apparent, linking the four films together to create an expanded meaning.

Producer: Feyzullah Yeşilkaya

Head of production: Mustafa Emin Büyükcoşkun

Cinematographer: Joanna Piechotta

Sound design: David Loscher

Bronze Baba

20 cm x 8 cm x 8 cm, (2016)

The eponymous figure from the computer game Baba World.

La Journée Sera Rude

Caran d’ache, steel, plastic (2017)

The title is a reference to Robert-François Damiens, a man who attempted to assassinate Louis XV in 1757. He was the last person to be drawn and quartered in France. The execution caused a major uproar among the French population for its extreme brutality. Foucault writes about it in ‘Discipline and Punish’. Damiens is supposed to have said “La journée sera rude.” (“Today will be tough.”) as he was led out of his jail cell to be executed.

Day Dream Machine

Wood, aluminium, leather,3D animation, steel, smoke (2018)

This kinetic installation with a cake-like appearance, adorned by white opium pipes produces smoke clouds in which various images appear. 18th century dungeon beds are attached to the surrounding walls. Violent mirages of dismemberment and hanging executions intermingle with sequences of a more pleasant character such as rotating flowers and pastries.

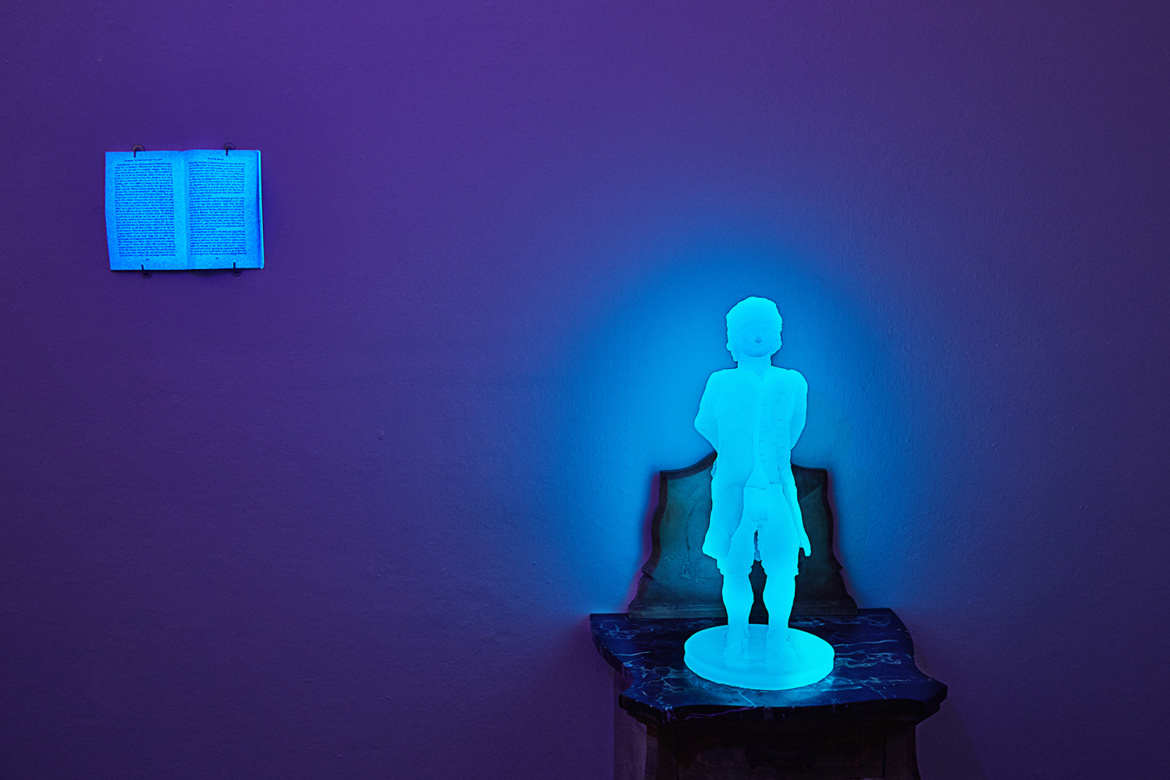

Glow-in-the-dark Rousseau

Polyurethane & glow-in-the-dark-pigment, 55 cm x 15 cm x 14 cm (2017)

“From the time on I recovered my peace of mind and something akin to happiness. Whatever our situation, it is only self-love that can make us constantly unhappy. When it is silent and we listen to the voice of reason, this can console us in the end for all the misfortunes which it was not in our power to avoid. Indeed it makes them disappear, in so far as they have no immediate effect on us, for one can be sure of avoiding their worst buffets by ceasing to take any notice of them. They are as nothing to the person who ignores them. Insults, reprisals, offences, injuries, injustices are all nothing to the man who sees in the hardships he suffers nothing but the hardships themselves and not the intention behind them, and whose place in his own self-esteem does not depend on the good-will of others. However men choose to regard me, they cannot change my essential being, and for all their power and all their secret plots I shall continue, whatever they do, to be what I am in spite of them. It is true that their attitude towards me has an influence on my material situation. The wall they have set up between us robs me of every source of subsistence or assistance in my old age, and my time of need. It makes even money useless t0 me, since money cannot buy the help I need, and there is no intercourse, no mutual aid, no communication between us. Alone in their midst, I have only myself to fall back on, and this is a feeble support at my age and in my situation. These are great misfortunes, but they are no longer so painful to me now that I have learned to endure them patiently. There are not many things that we really need. Forethought and imagination multiply their number, and it is these unceasing cares which make us anxious and unhappy, But I, even if I know that I shall suffer tomorrow, can be content as long as I am not suffering today. I am not affected by the ills I foresee, but only by those I feel, and this reduces them to very little. Solitary, sick, and left aloen in my bed, I could die there of poverty, cold and hunger without anyone caring. But what does it matter if I myself do not care and am no more affected than the rest of them by my fate, whatever it may be? Is it such a small achievement, particularly at my age, to have learned to regard life and death, sickness and health, riches and poverty, fame and slander with equal indifference? All other old men worry about everything, nothing worries me. Whatever may happen, I do not care, and this indifference is not the work of my own wisdom, it is that of my enemies and compensates me for the evils they inflict upon me. In making me insensible to adversity they have done me more good than if they had spared me its blows. If I did not experience it I might still fear it, but now that I have subdued it I have no more cause to fear. In the midst of my afflictions this disposition gives free rein to my natural nonchalance almost as completely as if I were living in the most totalt prosperity. Apart from the brief moments when the objects around me recall my most painful anxieties, all the rest of the time, following the promptings of my natural affections, my heart continues to feed on the emotions for which it was created, and I enjoy them and share them with me, just as if those beings really existed. They exist for me, their creator, and I have no fear that they will betray or abandon me; they will last as long as my misfortunes and will suffice to make me forget them. Everything brings me back to the sweet and happy life for which I was born; I spend three-quarters of my life either busy with instructive and even pleasant objects, to which it is a joy to devote my mind and my senses, or with the children of my imagination, the creatures if my heart’s desire, whose presence satisfies its yearnings, or else alone with myself, contented with myself and already enjoying the happiness which I feel I have deserved.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Reveries of the Solitary Walker

Eighth Walk

Pp. 130-131

(1782)

Exhibition text for “Phantasm”: A Lawnmower and a Soufflé by Deniz Eroglu

Ottoman Euro

Materials: leather, textile print, bordure,

Dimensions: 120 cm x 65 cm, (2016)

Louis XIV was the first European regent to invite the Ottomans to his court. In the wake of this cultural exchange, the French started implementing Ottoman style furniture in their royal quarters. The term turquerie derives from this period and refers to Turkish aesthetic elements as a constitutive component in furniture of the era. In French high society wearing turbans and caftans gradually became fashionable, as well as lying on rugs and cushions. This was also reflected in the art of the period. Music, paintings, architecture, and artifacts were frequently inspired by the Turkish and Ottoman styles and methods.

Sourced from sustainable local leather.

Baba Diptych

Media: SD Pal. Duration: 2:29 minutes, (2016)

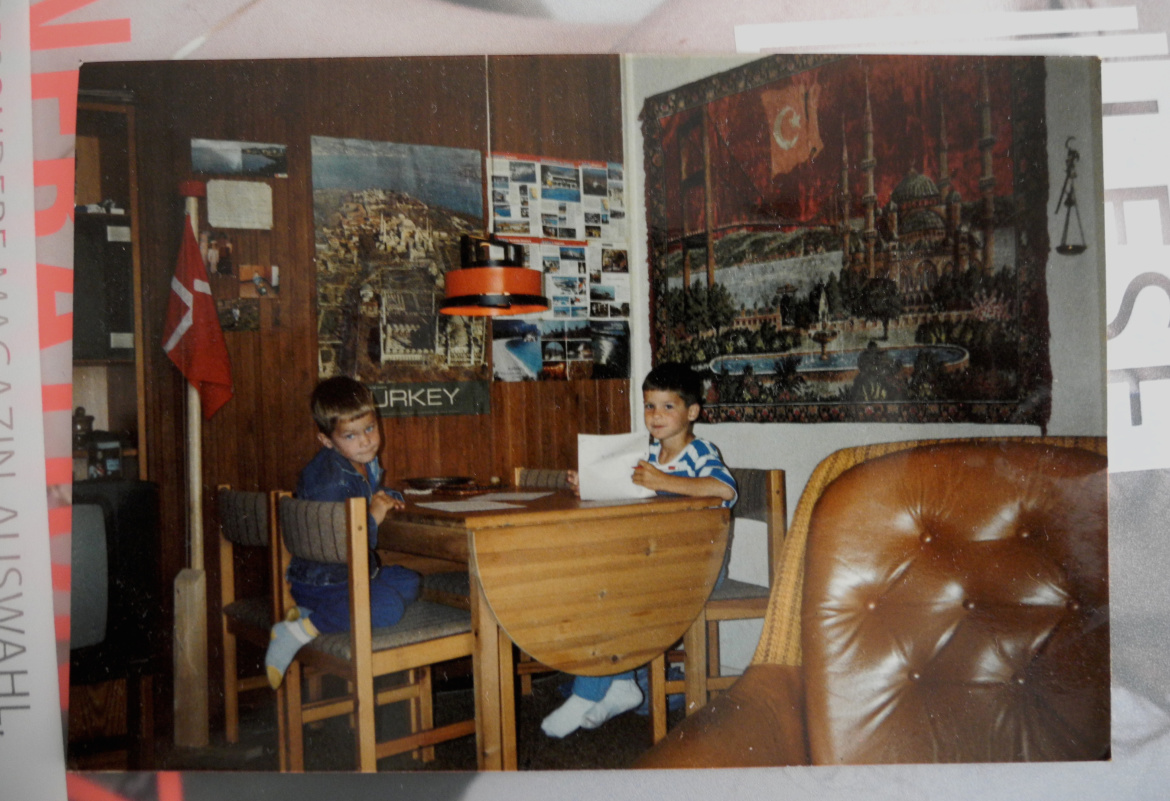

This work consists of a family home video filmed by the artist in 1996 juxtaposed with a replica of the video made by the artist twenty years later which was recorded with the same camera in the same location.

Kebab Vases

Materials: Hand blown glass, paint,

Dimensions: 75 cm x 40 cm, (2015)

Milk & Honey

Materials: polyurethane, honey,

Dimension: 20 m x 4 m

(2016)

From Overgaden’s “Milk & Honey” exhibition text:

The title Milk & Honey refers to a Danish TV programme on Turkish immigrant workers called The Land of Milk and Honey, which was broadcast on Danish state television in 1989. The artist watched the programme when he was eight, and remembers it having a negative impact on his relationship to his Turkish background. Eroglu has described the sadness and disappointment he felt when he realised that a lot of people in Denmark didn’t care much for the people who had stayed in the country after originally being invited to come here as temporary migrant workers.

The title of the exhibition also alludes to the dream of Denmark as a land of plenty, flowing with milk and honey. For generations many immigrants and refugees have come to Denmark with high hopes that have had to be adjusted in the face of a culture that was perhaps less friendly and welcoming than they had anticipated. The works in the exhibition therefore go beyond Deniz Eroglu’s personal family history, and can be read as a portrait of Danish society and the Danes’ treatment of ‘outsiders’ – people like Eroglu’s father, who came to Denmark in the late 1970s.

With this installation Eroglu has created a veritable land of milk & honey consisting of sticky oversize Danish crowns and a pulsating milky river reminiscent of industrial food troughs typically used in Danish pig farms.

Baba World

Computer game, (2016)

Literally a playful work wrapped in retro aesthetics, Baba World transports us directly back to childhood memories, as we play a Super Mario inspired game that features Baba as the main character and hero. Super Baba not only has to collect as many coins as possible but also skilfully escape the piggish menace. The painstakingly accumulated wealth of our jump-and- run hero is directly deducted from the Danish state treasury but one wrong step, be it an encounter with a sinful pig or the fiery lavas of hell the treasure hunt of the immigrant ends abruptly and Super Baba ascends to heaven.

Exhibition text for “Milk & Honey”: A Twinkle and a Tear by Laura Amann

Exhibition text for “This city on the seashore, they say it is built of marble”

Press release from ‘This city on the seashore, they say it is built of marble’ at “Frankfurt am Main”, Wildenbruchstraße 15, Berlin

November 16 – December 13 2015

“It was brought by a relative from Germany who came to visit me in Denmark.

He bought it in Germany. There was the motif of the Grand Mecidiye Mosque on the carpet. The view of Bosphorus on it was mesmerizing.

Seeing the carpet on the wall would make one feel like living in tune with Turkey.

The handmade tea-urn, Turkish coffee cups, handmade Turkish vases added beauty to the house, so did the hand knotted carpet. Seeing furniture particular to Turkey in the house made us happy and at the same time astounded our guests.”

– Mustafa Eroğlu

Excerpt from ‘Swann’s Way’ by Marcel Proust:

“At a bend in the road I experienced, suddenly, that special pleasure, which bore no resemblance to any other, when I caught sight of the twin steeples of Martinville, on which the setting sun was playing, while the movement of the carriage and the windings of the road seemed to keep them continually changing their position; and then of a third steeple, that of Vieuxvicq, which, although separated from them by a hill and a valley, and rising from rather higher ground in the distance, appeared none the less to be standing by their side.

In ascertaining and noting the shape of their spires, the changes of aspect, the sunny warmth of their surfaces, I felt that I was not penetrating to the full depth of my impression, that something more lay behind that mobility, that luminosity, something which they seemed at once to contain and to conceal.

The steeples appeared so distant, and we ourselves seemed to come so little nearer them, that I was astonished when, a few minutes later, we drew up outside the church of Martinville. I did not know the reason for the pleasure which I had found in seeing them upon the horizon, and the business of trying to find out what that reason was seemed to me irksome; I wished only to keep in reserve in my brain those converging lines, moving in the sunshine, and, for the time being, to think of them no more. And it is probable that, had I done so, those two steeples would have vanished for ever, in a great medley of trees and roofs and scents and sounds which I had noticed and set apart on account of the obscure sense of pleasure which they gave me, but without ever exploring them more fully. I got down from the box to talk to my parents while we were waiting for the Doctor to reappear. Then it was time to start; I climbed up again to my place, turning my head to look back, once more, at my steeples, of which, a little later, I caught a farewell glimpse at a turn in the road. The coachman, who seemed little inclined for conversation, having barely acknowledged my remarks, I was obliged, in default of other society, to fall back on my own, and to attempt to recapture the vision of my steeples. And presently their outlines and their sunlit surface, as though they had been a sort of rind, were stripped apart; a little of what they had concealed from me became apparent; an idea came into my mind which had not existed for me a moment earlier, framed itself in words in my head; and the pleasure with which the first sight of them, just now, had filled me was so much enhanced that, overpowered by a sort of intoxication, I could no longer think of anything but them. At this point, although we had now travelled a long way from Martinville, I turned my head and caught sight of them again, quite black this time, for the sun had meanwhile set. Every few minutes a turn in the road would sweep them out of sight; then they shewed themselves for the last time, and so I saw them no more.

Without admitting to myself that what lay buried within the steeples of Martinville must be something analogous to a charming phrase, since it was in the form of words which gave me pleasure that it had appeared to me, I borrowed a pencil and some paper from the Doctor, and composed, in spite of the jolting of the carriage, to appease my conscience and to satisfy my enthusiasm, the following little fragment, which I have since discovered, and now reproduce, with only a slight revision here and there.

______

Alone, rising from the level of the plain, and seemingly lost in that expanse of open country, climbed to the sky the twin steeples of Martinville. Presently we saw three: springing into position confronting them by a daring volt, a third, a dilatory steeple, that of Vieuxvicq, was come to join them. The minutes passed, we were moving rapidly, and yet the three steeples were always a long way ahead of us, like three birds perched upon the plain, motionless and conspicuous in the sunlight. Then the steeple of Vieuxvicq withdrew, took its proper distance, and the steeples of Martinville remained alone, gilded by the light of the setting sun, which, even at that distance, I could see playing and smiling upon their sloped sides. We had been so long in approaching them that I was thinking of the time that must still elapse before we could reach them when, of a sudden, the carriage, having turned a corner, set us down at their feet; and they had flung themselves so abruptly in our path that we had barely time to stop before being dashed against the porch of the church.”

SINGING KEBAB & SINGING BABA

Two-channel installation, 3D Animation & VHS, 2 x 2 minutes, (2015)

Video installation consisting of two screens facing each other on loop.

In 1995 I filmed my father singing a Turkish song on camera without knowing that the song contained a message for me. In 2015 I made a video work about a singing kebab in which I sing a song back to my father. Two monitors are placed across from each other and thus a dialogue is created that spans time and culture, a dialogue between my father and I.

Artist Talk at Polistar Istanbul

Conversation between Didem Yazici and Deniz Eroglu at Polistar in Istanbul the 17th of September 2013

Didem Yazici: Welcome to Polistar. I am happy to introduce Deniz Eroglu sitting next to me right now. He is the artist of this solo exhibition. His first solo exhibition actually that I curated.

Last night we had the opening of the show. And there was no speech at all. No text. We believe that the exhibition should speak for itself and then we have the reflections and the conversation the next day.

So the space we are sitting in contains the main work of the exhibition The Bedridden Triptych. I assume that you have all watched it already or?

So I would like to start with this work. But before should I give a short introduction to the biography of Deniz Eroglu? I would like to share his biography, because I think it will be helpful in understanding his work. He lives and works in Frankfurt and Copenhagen. Eroglu focuses on the medium of film and video as you can also see in the show. After completing his bachelor of fine arts from Funen Art Academy in Denmark he continued his studies and artistic research at Städelschule in Frankfurt in the class of Douglas Gordon, where he was awarded an honor recently, the Engel & Völkers Prize.

Departing from an experimental modus his works have gradually found a more cinematic expression through collaborations with cinematographers and actors. His work has been shown internationally in exhibitions as well as film festivals.

So let’s start with the Bedridden Triptych which is Deniz’ most recent work. Each film here represents a different style of filmmaking. And each of the three films has a story, and each of them presents a different period of a lifetime. Birth, adulthood, and old age. So I would like to hear. How do you then connect the different styles with the timeline? Because here we see this figure acting like a child [the first film]. So all of these references how are they relating with the language of the film? If you look at the last film in the Triptych there is a very Bergmanesque approach.

Deniz Eroglu: I would say that in my work I refer a lot to film language. I have watched a lot of films. Old films. I have been very inspired by those things that I have seen and I have tried to use film language within a fine art context.

So I think a lot about how to do that, how to find my own voice. I look at numerous directors, also video artists, how they do this, and then one of reasons why I started working on this [The Bedridden Triptych] and one of the reasons why this idea appealed to me was because here I could suspend all of these ideas I have personally, my personal preferences, and instead make three films that were not an expression of how I would necessarily choose to make a film. I don’t deal with cinema verité. I wouldn’t necessarily want to shoot in SD (standard definition) or cinemascope.

So I made these films where I paraphrased a lot film aesthetics, film language styles that I have seen myself. And I did that to show different aspects of the state of being bedridden. The works I have made prior to this and I guess we will talk about that later are all about people who try to transgress the humanly possible. Like how can we find meaning in our lives, how can we instill our lives with meaning, so there is something to live for? And here I kind of went the other way, where I said: ok, these characters will negate. They will say: “No, I don’t think there is anything I can do.” More or less. “Maybe I can reflect, but it stops there. Or it will stay like this.” So all of these humans that we see in the work for different reasons, you can say that it’s all a negation of life that we are witnessing. They say: “No, I have my world here, my life here. I don’t care about anything else.” And still these three men exist under different circumstances, or their respective predicaments are very different. So by making these three films in three different styles I could show different aspects of being bedridden.

Personally I like to stay in bed on Sundays and watch films projected on the wall. It feels like a very sorrowless activity to engage in. There is a world of difference between that and being ill and old and having to stay in bed like the man in the third part of the triptych for instance.

And so you could say for instance in this film [the first film] that it plays with comedy in a way.

Benny Hill that you are all familiar with is one of the references. Here we have a more comical aspect on the state of being bedridden.

DY: Last night we were having a conversation during the opening and you were telling me about the book you read by Jean-Luc Nancy, ‘Tombe de Sommeil’. And you said you were referencing that in the middle piece, that there is some heavy influences. Maybe you could elaborate on that and share with the audience?

DE: Yes, of course. So I read a book about 7 years ago by Jean-Luc Nancy called ‘Tombe de Sommeil’. It’s an essay about sleep. And so that book gave me the idea for the film in the middle more or less. So that was what sort of spurred it. And I started thinking about the film and I wrote a first draft for the script and then I was confronted with a problem: how to make a film that is visually interesting, when the characters are immobile? They stay in bed the whole time. How could I make something that would be interesting for people to watch? And this is when this idea came to me of having different styles, so I have this notion, I watch a lot of films as I mentioned, and I feel like often times if the director is succesful with what he does he is able to create something thus far unseen or unknown to us. Tarkovsky said “Some people can imitate reality while others, the great artists, they create their own realities.” I like that notion of creating your own reality. I would like to believe that this is the way that film as an art form works. I don’t believe in realism, I don’t believe in a representation of a “reality” that we can agree on. I would say I believe in creating different “individual realities” you could call it. Here I tried to do that, to create three worlds. A world of sorrowlesness [the first film], a world of self aggrandizement [the second film], and a world of complete resignation in the black and white film [the third film]. So these films on the sides [first and third films] are 15 minutes each and the centerpiece is about 30 minutes. I think together they convey something. The three films together juxtaposed will give you a sense of – hopefully – you know that things are different for everybody.

DY: And there is a clear idea with the structure of the triptych here, the reference to the cosmos. It is a concept that Deniz uses not only in this work, but actually each piece in this exhibition have references to a cosmology. And here the sculptural piece [a ceramic vase] and you see the Milky way [a printout of the Milky Way]. And the presence of symbols of eternity in the films.

And these objects are all from the films, so they exist, they are used in the films. While we were preparing the show we were discussing whether we should show them or not, because they already exist in the film. What is the relation when you show them? You have a moment of hesitation, is it too much? But then we concluded that is was better that we included it, to accentuate something very important about Deniz’ practice. It would be very interesting to hear the story of these objects and also the position of cosmos in your work in general. Maybe you could start by telling us why showing the objects is important to you? The physicality of it.

DE: Physicality is an important word in this context. First of all I would say I don’t know if this is necessarily a symbol of infinity, but as you can all see obviously it’s two canes taped together. In the first film he uses this to get things around the room. And then as I made these objects like someone else has probably done before for practical reasons, perhaps some Indian one-legged person in the streets of New Delhi, who knows. It occurred to me that this pattern – the sway – [the round shape of the canes] it’s sort of reminiscent to me of the milky way, they have a galactic shape sort of. It was the idea of hanging these two things across from each other. And then of course another thought that comes to mind, I have watched a lot of documentaries about people who live this kind of lifestyle. Either due to obesity or mental illness and I guess we could imagine if we live our lives in a small apartment somewhere we start to see things. You are shrouded, you are in this little kingdom, this little cosmos by yourself. So when I imagined these things, when I envisaged these things, I took it into consideration that there would be objects perhaps that would be very important to them as a very intricate part of their lives. Objects that have a special status or value to them. These films are connected in various ways. For instance in the middle piece you can see this man eating now. He is having a dish with with red meat, green peas and brown gravy and potatoes. This is what they all eat in the films, they are having the same course. There is a connection like that, but there are also these connections of these cosmic symbols in these works.

Audience: You play with the timing at all?

DE: They are not exactly 15 minutes each, so they alternate during the day. Sometimes the connections are there in various ways. So it plays itself out in various ways.

DY: And maybe I would like to move on now to other works that are shown in the adjoining room.

Sons of Illumination was the first work I saw from you, and I hugely admired the film and actually this work was the starting point for making this exhibition. There is an element in the film that is highly poetic that is inspired by the philosophical approach of Rumi.

So I am quite interested in your relation to poetry, because I mean the text in the film, if you watch it carefully, all these whispers it’s actually a poem, and I read the whole film also as poem consisting of moving images. The part that especially strikes me, “When the fruit is ripe it falls from the tree.” But before that it says “Time has come to leave everything behind.”

[She reads the text in Turkish the way it appears in the film]

I was like I wasn’t sure if it was Deniz’ text or a quote from Rumi, because it’s really good. I know there are quotations from Rumi.

DE: Not directly.

DY: But I was confused. There was this sort of ambiguity. And then we spoke about it, and Deniz actually wrote it. And so that is the first thing, that you write it as a poem. And also the title of the exhibition derives from a poem by Rimbaud, Towards the Garden of Palms. But maybe we go bit by bit. But it’s an important element to get. Maybe you can elaborate on The Sons of Illumination. How do you relate to poetry within this process of filmmaking?

DE: I think a lot about what are the unique qualities of film. How can I communicate things through moving images besides the banality of a story. I don’t want to hear any stories. Maybe that’s great when you’re a child growing up. But personally I am fed up with stories in the sense that you go to the cinema and you know what is going to happen. That is not interesting for me. And that is where poetry becomes interesting as a way of opening up for something more than a story, or allowing for more than the recounting of a story. I used to take classes in literature at Copenhagen university. First and foremost French literature a couple of years ago, before I started studying art and I learned a lot from that. It was very interesting. The professor there said “It doesn’t necessarily have to make sense.” I think a lot of people are frustrated with poetry for that reason. During that time I discovered poems that I really loved and that have been with me ever since. And it’s true what you are saying that this exhibition title comes from Rimbaud. It’s a line from a poem I read about ten years ago. It’s called Royauté or Royalty in English. And my next work will be called Towards the Garden of Palms. So I personally feel like if you ask about my personal inclination towards poetry, that there are certain poems that mean something to me and I am always searching for other poems to expand this repertoire that I carry around in my mind. And these poems I will return to again and again and I will live with them. This is what I tried to do in this film Sons of Illumination. It took me a year to write this text. And I was inspired by Rumi as you said, but also the Vedas.

Audience: Why do you not like stories? Many stories would elaborate a poem.

DE: I am talking about cinema. When it comes to cinema I don’t think that storytelling is interesting. I can watch a film by someone and enjoy the narrative, but I feel like when it comes to creating new works that are interesting, narrative is something I don’t find interesting. Also in literature I enjoy narrative of course, like Thomas Mann or whatever. I feel like storytelling when you see it in a conventional way very often is very narrow. Of course I also employ storytelling in a certain sense, but I try to expand its possibilities. But I am talking about storytelling in a very conventional, strict sense and I don’t think that is interesting.

Audience: But you can play with the kind of mundaneness of the story, because it is much more democratic than a poem. Which is fine, it is part of you. Somehow it is part of poetry that it is this kind of high level culture bourgeoisie. Like you use the vocabulary of high culture. And I think it’s also because you have this kind of attitude of “storytelling we can’t get anything new out of it.” I would disagree.

DE: Of course you can experiment with storytelling. When it comes to cinema I don’t think it’s interesting. I think cinema can do so much more than that. For instance if you look at Stan Brakhage. He is perhaps an extreme example, but I think that direction is much more interesting. I think we can still expand the territory of what moving images can convey.

DY: I think this is a quite clear statement from you. How you relate to poetry and take it as your reference point and I think it also shows your individual artistic approach. I believe it’s because you feel more free in the realm of poetry.

DE: But of course point A is connected to B. You have to take account of that, that’s ok I think. But I don’t like the conventional modes of storytelling that you see practised in 95% of what is put out.

Audience: But that everyone agrees on.

DE: I am not sure about that actually. I would love for it to expand, for this expansion to become the norm. In my field, video art or cinema, you can get more profound experiences out of the experiences that are offered to the audience rather than: “Oh A leads to B”.

Audience: But there is also visual standards in video art. If you look at this biennial that is going on [the Istanbul biennial 2013]. We also talked about the visual standards of biennial videos. Film, languages, subtitles, it’s all a vocabulary.

DE: I am only talking about the narrative. The chronology that is just tiresome and repetitive and not very inventive.

DY: Speaking about poetry I would like to read the poem from Rimbaud which is a reference of the exhibition. We did it at Documenta a lot with a David at Kassel with poetry readings. [Didem Yazici organised a poetry reading event during Documenta 13]

One fine morning, in the country of a very gentle people, a magnificent man and woman were shouting in the public square. “My friends, I want her to be queen!” “I want to be queen!” She was laughing and trembling. He spoke to their friends of revelation, of trials completed. They swooned against each other.

In fact they were regents for a whole morning as crimson hangings were raised against the houses, and for the whole afternoon, as they moved towards gardens of palm trees.

So I think reading the poem is really important. It’s a way to make manifest here among us.

Can you please explain to us the connection you have to this particular poem?

DE: There are many reasons why this poem appeals to me. I think there is a strain that I recognize in my own work. “I want you to be queen.” That sentiment of I want to go further. I want to go beyond the possible. I will make you queen. She wants to be queen. She is excited. And they joyously walk through the garden. I see that in the characters that inhabit my work too. They want to create these larger-than-life projects and go beyond. And I feel that myself that I really strive also to create, or like to move beyond and try to instill my life with meaning. Like all of us, and I am sure that everybody that goes to look at art that is also what that is about in a way. You are looking for something to give you something. Maybe that is what brought you here today, the hope that this could give you something. I have this experience often that it doesn’t give me anything though (laughter).

DY: The last point I would like to make is about ambiguity. Each work has a certain ambiguity for instance if you look at Der Geist des Lebens, it appears as if there is this found material, an old artist, this whole narration around it. 7 artists and scientists come together to produce a work, a final work, a dance, a choreography that conveys the meaning of the universe, the cosmos. But there is this ambiguity because you don’t know if it’s really a found material or did you film it yourself. It was quite interesting, during the opening a lot of people came to ask if this is real or not. Also with the Bedridden Triptych, people were like “Is this a documentary? How did you find these people?” And Deniz was like: “No, they are actors.” And even me working for the show, working for the exhibition, and going through the texts, even in the texts for the work it is not clear. The text for Der Geist Des Lebens [The Spirit of Life] doesn’t say that it is all fictional. It pretends that it’s found material from the old artist and it seems as if you put something on top of it. Maybe we can finish the conversation on this subject? If you say something about the ambiguity and maybe you can also say something about your next work?

DE: So I think we all know that when it comes to visual art and cinema there is a lot of artificiality present in a film. There is a lot of different styles. Often we have the accompaniment of violins or something like that, that sort of heightens the impression you get, the sensory impressions that enter your brain. I am not personally fond of those effects when it comes to my work, the way I envisage my work I prefer to steer clear of artificiality like that. I try to avoid that there is a lot of like acting going on. Like with fiction you have a contract, you know it’s fiction and they’re acting and it’s very extreme, I don’t like that. For instance with Sons of Illumination people ask me to my surprise “Did you live with these monks? Where did you find them?” and so on. And I made it consciously to appear like an old anthropological film from the seventies shot on a Bolex camera. But that is one of the purposes of “my game” that I choose. For instance the middle piece looks like a documentary, but as Didem said just now, it’s an enactment with a script and so on. It opens up to other possibilities, when you try to make it look like “something real” instead of something fictional where the audience have to enter into this contract with you of: we know it’s fictional, but let’s pretend it’s real.

Audience: So you play with these different modes of representing these kind of things in reality?

DE: Yes, exactly. We present it like that, we have these languages, and these contracts that we are aware of, but with some of my works I blur that boundary or the “contract”. So it might look fake, but it’s potentially hard to pinpoint whether it’s real or not. I play kispus with you in that sense.

Audience: But you can also say that all exhibitions are fake like that. But to me this exhibition also looks very much like an exhibition taking place in 2013.

DE: I don’t have an overview of art in that way to be able to say if this is very 2013. I would say that I am interested in art of course, I study art, but I don’t know. You tell me. I just make the works, I go away for many months by myself to conjure up these ideas. I don’t make statistics on what other people are producing.

Audience: I mean you could take this there and that there [points at the sculptures] and put it in a Berlin gallery and people would love it, because it looks very 2013.

DY: I really don’t believe in those superficial standards. I see your point, but this show really developed from very organic conversations and I think it’s very important that the show takes place in a non-profit space, and it doesn’t really try to imitate the sort of language of these ways of doing it with profit in mind.

DE: The thing is also I just put this up the way I envisioned it. I came here a couple of months ago. And then you can ask why did you do that? And that’s ok with me if you believe me or not, or believe I have the integrity or not. That’s totally up to you. You choose. You decide. I put up the works, I decided to do it like that.

DY: And I would like to add, that I don’t believe in this idea of “the exhibitions of 2013”. If you look at Documenta for instance, you can say “Oh 2013 is about the organic, about plants.” That is a superficial understanding of what the “contemporary” is. I worked at the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart and we showed ceramics. And we were like so into the contemporalization of the material. It’s good that you are mentioning it, because I think that term “a 2013 exhibition” is highly problematic.

Audience: But he was talking about the videos, like quoting specific modes of visualizing these kinds of things.

DE: But there is a difference between that and then saying that I have a business plan for how the exhibition should look.

Audience: Ok. I was asking. There was no plan for the show?

DE: No specific plan, no.

Audience: For me it just seems like the most standard way to show art. And in that way it tries to not ask a question about the form of the exhibition. It just takes a standard and it just does that. And in this way it is for me, it’s not 2013, but it’s art for the past thirty years. It’s how to present art within a white wall space. And somehow it’s like it’s interesting. I’m interested why you say you are against a lot of things, but then you do them. Like you say “I am against cinema verité, but I am into naturalism.” What is the difference between these two? Why would you say you are against something and then do it?

DE: Cinema verité and naturalism is not the same. Cinema verité pressuposes that you can actually record reality. I don’t believe in that. Not for a second. There is no such thing as recorded reality, there is no such thing as one singular aspect. This is a point that I try to make here. There is no singular aspect. There is only our imaginary ideas of the world. Your perception. My perception. They are different things. And I never said I was into naturalism.

Audience: No, but it’s more the idea that you end up making something that looks real.

DE: But this is the condition of the game that I have chosen. This is what I have told all of the actors. They said: “Why are we doing it like this?” I said: “These are the rules that I have made up for this game that we are going to play now.” And then I just play with those formats. I don’t believe in them. And to me I would say it should be quite clear, since I have made three different films that I don’t believe in them. As I said before I felt like this was an emancipation in the sense that in my other films I am very meticulous about how I want to represent this in “the best way” or whatever you want to call it. And then it was so nice to just make three films that I made, but in a sense I didn’t make them. They don’t represent my taste or sensibility. But together they form an amalgam of perspectives on a specific state, the state of being bedridden. I told the cinematographer when we were making the middle piece [the second film] to “shoot it like you have down’s syndrome. Just zoom in and out. Just fuck everything up.” And this film too [ points at the first film] is expressive in the way that we mounted the camera on these big poles that he uses like ridiculous POV’s. A lot of bad taste. But it was nice to do that. I don’t believe in bad taste, but I can make a representation of bad taste, when it is juxtaposed with the other films. And then I made that [points at the third film] and someone said “Oh I watched your films, and the last film when I saw that I really liked it”, because it is tasteful in a sense. It’s cinemascope. Most people agree it’s a tasteful, beautiful format. And the film is shot in black and white on nice film stock. The lighting if you look now for instance is very meticulous lighting. The whole thing is beautiful, it seduces the audience. And then they like it. But I don’t believe in seduction. I think seduction is an enemy of what I am trying to do.

Audience: So you don’t believe in it, but you use it to show that you don’t believe in it?

DE: I don’t use it to show that I don’t believe in it. But I think there is something interesting in the juxtaposition of the three works. And then you’ll say “But what is this guy trying to do to me?” I don’t know. I’m not going to tell you what you are thinking and what to devise. But this was my idea, when people meet this. That they will go “Hmmmm what is the meaning of this?”. You see this with bad films with a conventional narrative that very often they try to seduce you. And they can seduce you even if you are a smart person and you walk into a cinema, because it’s so powerful they can seduce you. Cinema is extremely seductive and this is what it can do, and that is what I am criticizing. Bad films take you hostage, but after you realize it was a lot of empty calories. All the explosions, violins and tears. This part of the triptych [the third film] has seductive elements. But this is one of the points I am trying to make for sure with all these slow dolly movements and so on. Who cares about the dolly moving? I care about questions. Formulating questions. And it’s very difficult. How do you choose to formulate it? It’s very difficult.

DY: I think that it is also a matter of methodology. The dolly is really a tool for you to convey an idea.

DE: But you are making a good point in a way, because doing something I am against, maybe it is better to just stop. But still I am doing it. Maybe I’m doing it, like this is a way out for me, this a way to find meaning. This is a way to reach other humans.

Audience: It’s very much with the interest of presenting what you have studied. And it’s your embodiment of that, and you are communicating your ideas through these mediums so you are trying to destroy, to show the way that they are made.

DE: But no, but there is more than that. It’s more than just showing the formats. It’s not merely a formalistic investigation. There is a lot of stuff to consider if you take your time to look at it.

Audience: Of course.

DE: So I would say it’s not about showing what I have studied, this is about showing what I have lived, because I believe the only way I can make these works, and I am not saying they are good works, but the only way I can make this is by going away and living a very special kind of lifestyle where I spend a lot of time by myself. This is the only way I can live this. This is the only way I can have thoughts that I think might be interesting to other people such as you.

DY: Going back to this conversation that I had yesterday. The things we have been discussing now sounds kind of abstract, but when I watch it I immediately relate to my bedridden grandmother. We all study and experience something and that ends up in our work. If we use the word ‘ego’ we should be really careful. I would refer more to the cosmos in the Sons of Illumination. You see philosophy, it is really about forgetting yourself. I think all of these elements are quite important. And another thing, when we think of contemporary art video film language, we hear often that the artists that make the films when there is poetry related to it, they recite the poems themselves, and sometimes it is too much. There is good examples of it. But it is something that is critiziced that it becomes too egoistic. So I also appreciate that you wrote the text [the text in Sons of Illumination], but you let others read to give it a different sound, a different voice. Are there anymore questions? Or anything we might like to know?

Audience: I would like to ask a question about the voice in terms of what you just said about the voice of the actors versus the voices of the people who live like this. Can you talk about your research for this film?

DE: It’s interesting that you should use a word such as voice. They don’t really speak in the first and the third film. So what came to me was more like these mute characters. In the first film he is a sort of Robinson Crusoe. It’s not a deserted island, or maybe the room is his island or the bed. So it’s about this mute character who is very inventive. One of the references is Malone Dies by Samuel Beckett. The third film I tried to create a sort of ghost. Also a mute resignation. So it’t not based on strict research about how people cope with illness. It’s not based on a script. It’s very spontaneous. But in the middle piece there was more research when it came to welfare and health care in the Danish state. What they can provide. There is this notion that the aid that you get from state has been diminished somewhat. It takes place in 1987. It’s like a midnight program for grown ups. A New Ageesque program called between Heaven and Earth [Mellem Himmel og Jord]. It’s a program that actually existed albeit in another form in the eighties in Denmark that I grew up watching. This character is some sort of anachronism that I imagined lived back then, in a time when you really had free access to all kinds of benefits from the state. It’s not like that anymore. But anyways I looked into that. And then there is a lot of film references, but not only when it comes to the performance. But I would say a major reference point is a film called Breathing Lessons. A documentary from 1996 that won an Oscar for best short subject documentary. It’s about 33 minutes, directed by Jessica Yu. She also made a documentary about Henry Darger [the art brut artist]. Breathing Lessons is about a man with polio who lived in an iron lung. He had a picture of the milky way taped to his ceiling [like the man in the third film]. It also inspired me a lot when it comes to the middle film. I helped me to understand the conundrum of being disabled and the insanity, the enormous black grief of being different and disabled and the inability to be grateful for life sometimes. And this man in the film even wrote poems and he recites them in the film. He says:”I fantasize about gunning people down in the streets. Why did they get this life that I can’t have?” And he talks about how he falls in love with some of his caretakers. “Beautiful strong legs and thick thighs.” and so on, which is what he can see from his iron lung when he is wheeled around. But here of course it’s in a more comical form.

Audience: Have you already talked about the objects?

DE: So I have these great poles. It’s a shame to admit this, but we wanted to bring them here to Istanbul, but in the end this exhibition was organized rather hastily, so we didn’t have enough funding to bring them. But I wanted to bring them, because this was a very integral and important part of the idea from the beginning. To create something that was visible. Physicality, I have used that word before. And these thick poles. I made them with a man who is a great carpenter and we hand chisseled the handles and everything and gave them different varnishes. And they look beautiful now, to me. I would have loved to hang them here. To me they look like some sort of strange residue from an Inuit culture the never existed. Like one has a hook, so it looks like a whale catcher’s tool. And they have aged now for a year, and they look beautiful now. It was the initial idea to bring them and hang them here. And these other objects also made sense. I found this in Morocco. I came across these ceramic works there.

DY: But you were looking for it.

DE: Yes, this was for the film. I knew I was going to get a spit tray. I was looking for a sort of cosmic symbol. I would say that maybe I imagined a golden or a brass object, but then when I saw this I thought: “Ah this is a nice representation.”I’m sure we have all had this thought that we are these microscopic creatures roaming around. This object has a form that is sort of reminiscent of the galaxy. I liked the idea of these characters being confined, but then the idea of an endless universe is present in their minds. And in the work I tried to allude towards that. That there is a void. One of the ways I did that was by placing the three films in different time periods. 60’s, 70’s and the 80’s. That is funny to me in a very dark way. I like to use humor. I will say something general now, but I think there is a lot of art that is too serious. That is maybe not the right word. Minimal, serious. Sometimes I get the feeling that many artists are concerned about risking anything in fear of uttering something erroneous. I don’t know if people are too afraid to risk anything. To risk making the argument. I want to do that however, even if that means I’m being irrational or making mistakes. And I want to use humor.

Audience: So these are humor elements on the wall?

DE: I would say that there are comical aspects to them. In the same way that you see humor in a book by Beckett.

Audience: It’s hard for me, because I see a reference to art of another time. Because there are two works I’m thinking of very specifically that are almost exact, like almost identical. One is from the Netherlands from the sixties, but it is with this wrapped up paper around two canes connected, but end to end with the same shape. And also work from Croatia with two canes that are fixed together. And the cane has this repetition within Dada. And it’s funny because there is this old man feeling.

DE: I think there is that element in the exhibition, connected to the work, but I can live with that. Of course when you do something this simple, it will resonate with other works from the past. Of course with Dada I see exactly what you mean.

DY: And what is interesting here is the humor. I think the appearance of these objects and the role they play give them an added meaning in this work.

DE: When you watch all the work these things will occur to you: ah he used it for this. But if you look and you imagine maybe you will see the relation, maybe not, but I like that it is open like that.

DY: Also, I felt like working with Deniz closely in the last months for the exhibition here. This relation between the image of the Milky Way and the canes is not simple like: “oh this looks similar, let’s hang them together.” It’s not simple like that. His mind doesn’t work like that. He was thinking about the Milky Way. The shape of the Milky Way is similar to the canes. I showed him actually that the shape is similar. He was thinking more content wise, but when those material objects came together we were able to see these possibilities.

Audience: So are the objects necessary in the exhibition?

DE: You don’t need the objects per se. But I feel like why not expand a little bit? When you come in and you’re faced with this you’ll have an experience like when you are confronted with any sort of object. And then if you watch this [points at the triptych] maybe your idea of this this object, your perception of it will change. And I think it’s fun to play with those possibilities. That there is a dialogue going on between these things. This is the whole point of hanging it up, installing a group of works like this.

Audience: I don’t get this part. To me I thought they looked like art [the sculptures] because they were on the wall. It’s very simple, very stupid. It’s a gallery space so you put stuff on the wall and then it’s art. And these are props from the films and they are connected.

DE: But are they props? I wouldn’t call them props. I wouldn’t call this a simple prop, because there is more to it in my opinion. But you also have to take something into consideration. If you flip your mode of thought now. So if you took everything down now, so it’s empty. Hmmmm….

Audience: I would like to come back to these art eyes that I have. I come back. I have this paper that looks super arty. I have the gallery space, I have the text, I have the biography. I have all the vocabulary that I know. And then I enter and it turns into an art show, a real serious art show. And then I was interested in your opinion, if you play with these things are you also playing with the exhibition, with the curator. Maybe she’s fake? Because the biography of the curator is longer than that of the artist.

DY: Did you count the works? (Laughter)

Audience: This is all your game you know. So I was wondering if you concentrate on this exhibition or if there is a grander purpose. The biennial is also your thing [The Istanbul Biennial took place at the same time].

DY: When you argue about this fakeness we can go on and on. I think the question of ‘the fake’, that’s something that play a large role in Deniz’ works.

Audience: But you can call everything ambiguous. Every work of art is ambiguous. This is a good job you have. You can not give an answer.

DE: I could give you an answer. Maybe I’m just more simpleminded than you, but I don’t spiral out like that when I go to look at an exhibition. What is real? What is not real? But it’s not my job to tell you if it’s real or not. You have to figure that out. Some questions arose in your mind from seeing it it seems, so I have done my job. I’m not going to give you answers. You have to give yourself answers. I am just formulating some questions.

DY: I would like to make a comment on something that was said before. The works appear to be “real”, but it’s fake. And maybe is that what you mean? The whole exhibition is informative. We don’t necessarily try to sell the works, rather this exhibition was made in a non-profit space because we wanted to engage. I’m interested in communicating with human beings. I would like to tell where he comes from, how old is he. This information can be extremely boring, but I think in such a chaotic opening when people come and go, I want people to remember who he is, where he comes from. It was absolutely fascinating how people came and asked: how did you find these people? The actors play so naturally. When we were speaking about the work, Deniz was telling me: hey listen Didem, I didn’t ask him to do this. This happened naturally. It seems like there is this natural flow in the way these works convey their ideas. Also in the Spirit of Life when the old artist is cutting the roses, he said: “I didn’t ask him to do it. He cut them like that.” All of this adds another layer to the work. There is this logic to the work.

DE: Yeah and the logic is not an enactment where I say: “do this, don’t do this.” I feel like a lot of these works, where I presuppose that something is real, we found these 8 mm, 16 mm reels. It places some of the films in a limbo in between fake and real. It’s sort of fake, but it’s also sort of real. It’s sort of a strange mix. For instance in the scene that Didem was talking about where the protagonist is cutting flowers I just told him: “Smell the flowers. Do something in front of the camera.” And he puts the rose up into the camera lens. What I really love about that scene is the butler in the background who is smiling. Because it’s just fun. We are just playing around. I have just met these two guys a couple of weeks ago. And that’s real. I know the smile is real. And I wouldn’t have thought to ask him to smile. It would have been too much, but it’s just so convincing. That’s a good way to make films in my opinion. I think the first one that did that, that short circuited all this artificiality I talked about before was John Cassavetes. And other people have done that since. Where is doesn’t become a question of narrative anymore. And let’s not exclude narrative as completely useless, I just mean to say that Cassavetes, in my opinion, was the first one that said: “ok, we’re going to shift from the narrative and go into describing a state of being instead.” I think this is much more interesting, and this is much closer to what I regard to be the essence of cinema. What it can do. What is emblematic for cinema in comparison to other art forms? What is its unique potential as an art form? It doesn’t have to serve as a platform for storytelling. People have used it for that. You can use it for all kinds of purposes. But when it comes to really posing or formulating more abstract questions it’s much more interesting to go down the other path I think.

DY: Perhaps it’s a good moment to wrap up and have a glass of çay. Please feel free to continue the conversation. It has been a pleasure to collaborate with you on your first solo show. And again, thanks to everybody for coming.

The Ideal Cinematheque

‘The self-indulgence of an Artist’ by Deniz Eroglu

Chickens’ Journey

Digital Video, 4:3, 4 Minutes, (2007)

At the São Joaquim market in Bahia, 4 chickens are laying on the ground. They are wrapped tightly in newspaper with only their heads sticking out. The gaze of the camera patiently waits to see what will happen to them. When an old woman buys them we follow the chickens on a journey towards their destiny.

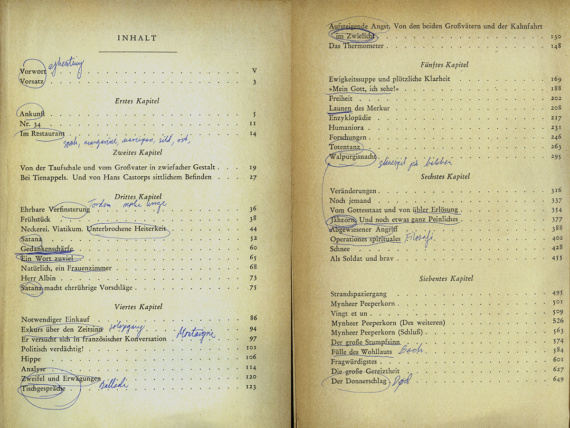

Der Geist Des Lebens

8 mm, 16 mm, 4:3, 16 minutes, (2010)

At the bottom of a sea chest in an old house lies a pile of dusty old super-8 reels waiting to tell the story of when the eccentric plutocrate Asger Bøgedahl invited seven artists and scientists from different parts of the world to participate in a symposium, whose aim was to unite science and art in one comprehensive work: a dance describing how the spirit of life was born from the cosmos. A triumph of the spirit, realised in its material form by the best minds within each field of practice.

Sons of Illumination

16 mm, 4:3, 6 minutes, (2010)

One man’s attempt to find solitude in the mountains joins him with unknown brethren.

In this imaginary parable elements from islamic mysticism are appropriated as a narrative unfolds; the formation of a religious movement starting out with one individual and growing into a fraternity with distinct ideas.

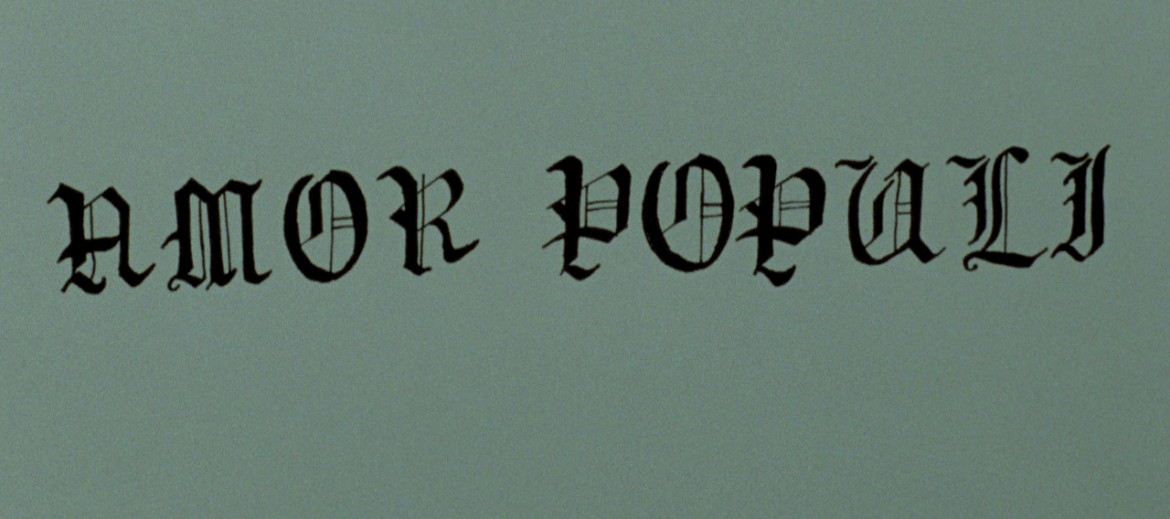

Amor Populi

16 mm, cinemascope, 6 minutes, (2011)

A man is running in a landscape of misty wetlands before dawn. Bloodhounds are howling in the distance. He is being chased. In exhausted resignation he falls to the ground and buries something. It is not long before his pursuers encircle him. Reasoning and forgiveness are out of the question. In a desperate plea for his life he sings a song of love.

Set in a distant time and place, this film is an investigation of the nature of violence prior to the “human rights” of Modernity and the ensuing ideas of “individual dignity”. The situation at hand is open: the specta- tor doesn’t know what happened prior to the confrontation.

Is the running man guilty of something? Or is he an innocent who has merely fallen victim to persecution?

Mountain Elegy

16 mm, 16:9, 14 minutes, (2012)

– In a landscape of barren snowy mountains a cave man (played by the artist’s brother) roams around in what appears to be pre-historic time. His primordial world is one of danger and one in which man lives solitary.

– A homeless man (played by the artist’s brother) falls victim to persecution as he is chased out of his village.

– A small film crew (the artist, his father, his brother and a cinematographer) sets camp in a small house on the side of a mountain. We follow the group as they set out to make a film, moving up the mountain through unhospitable winter landscapes.

This work is structured as an anachronic narration consisting of three “story lines”. It is a melancholic meditation on estrangement, non-place, communion and family ties.

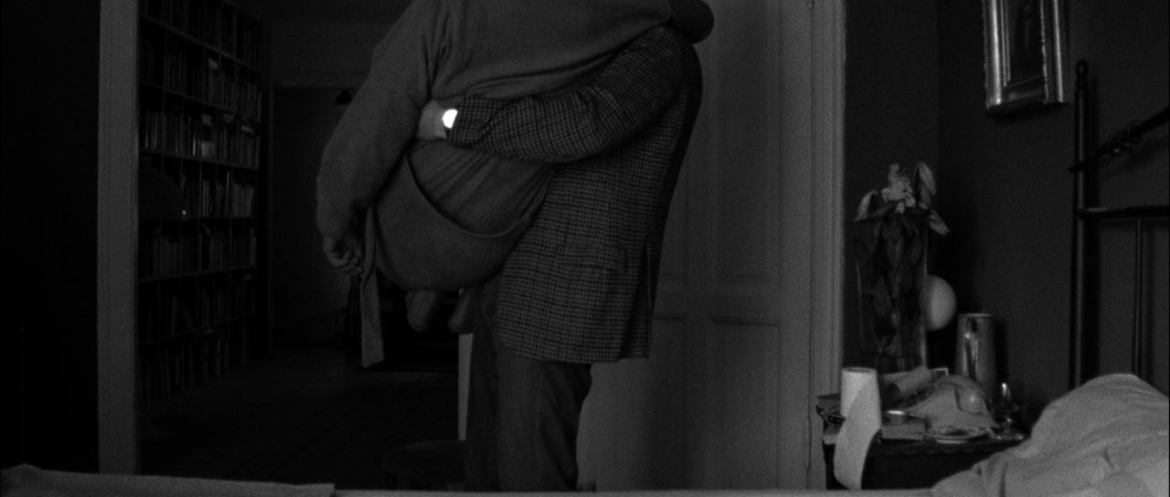

The Bedridden Triptych

The Bedridden Triptych – Contentment, Making Something of Oneself, Losing / Three-channel installation / 16 mm and VHS, 4:3, 16:9, cinemascope, 2013, 60 minutes

The state of being bedridden.

What allows for this phenomenon to occur? Indolence, poor health, old age? It can be hard to ascertain with certainty. In a sense one could say that life allows it to occur.

Suppose there is something eerily comical about the life of a person who resigns himself to this fate. Is there some amusement to be had as spectators to the ever churning mind of someone left to his own devices? Could it make us smile? Possibly.

But if we ourselves were to be put in this position, imagine the horror!

Through its references to historical film language constructs, the three films – as a combined whole – create an amalgamation of an existential cul-de-sac.

A dead end that has become the norm for the old, the unlucky and the ill in the industrialized countries of the Western hemisphere. It’s what lies in waiting for us if we live long enough.

From the CPH:DOX catalogue:

A practitioner, a prophet and a poor, tortured soul. Three protagonists, who for more or less articulate reasons have decided to spend their lives in bed, on the margin of the Danish welfare state – isolated from the world, which as the ‘Prophet’ puts it while he is being cared for by the municipality’s home carers, is nothing but a grand illusion.

Deniz Eroglu’s self produced film is structured as a triptych with three parts, which in spite of their large formal differences share a black-humoured , Beckett’esque view of the soaring soul’s troubles with the often extremely tangible prison of the body. Two of the segments are shot on 16 mm, while the more talkative center segment is shot directly on old VHS tapes and presented as one of those documentary ‘alternative world’ programmes that you could catch on TV after midnight in the 1980’s.

A film, whose director obviously spent his formative years in the company of everyone from Kafka, Orson Welles and Ingmar Bergman to ‘vidéo brut’ and conceptual film of the kind he has started to produce himself.

McMansion Man

Digital camera, 4:3, 30 minutes, (2014)

Thomas H aka Dos Equis aka The Dog Wizard is a man of many identities. He leads a free spirited, nomadic lifestyle with his canine entourage Bogey, Moschz and Ginger.

In Florida there is an astounding amount of houses for sale.

This has provided Thomas H with a unique method to secure a roof over his head. Boy does he have some tricks up his sleeve!

He moves into a house as a tenant under the presumed intention of wanting to buy it.

Soon the suit is put away and the djellaba is donned.

But the clock is always ticking: when the owner discovers he isn’t paying rent, measures for his eviction are set into motion.

This doesn’t discourage him in any way however.

With the vast amount of empty houses, this ingenious leader of the pack is always able to find a new domicile.

Towards the Garden of Palms

RED Epic, cinemascope, 70 minutes, (2014)

A wealthy man invites 6 guests to come and spend a week in his countryside estate located in strange foggy wetlands. Keeping a sharp eye on them is a rather ferocious dog and a pedantic butler. In the beginning it is not entirely clear why these people have been invited, or what the purpose of their stay is. Furthermore, to their surprise the house they are lodged in is old and dilapidated. They soon discover that it is expected of them to be the attentive audience as the host appears and presents his thoughts. His ideas are self-enamouring, verbose and melancholic and the whole experience is perceived to be a bit suffocating and pitiable. Why does he want to share all these thoughts? What is it he wants?

Taking literary cue from ensemble plays by Molière and Corneille as well as through cinematic iteirations of similar dynamics, this work is constructed much like “The Rules of the Game” by Jean Renoir and “Satántango” by Bela Tarr, where a group of people embody a movement towards a dramatic climax.

The film work interrelates with text based and photographic works as well as sculptures and found objects.

Video Video – Essay by Mads B. Mikkelsen (Danish language)

Video video

En ny bølge af ikonoklastiske film optaget på analog video gør front mod den digitale perfektionisme – og mod den moderne kvalitetstradition

Af Mads B. Mikkelsen

Robert Bresson giver i sine Notes sur le cinématographe et bud på, hvornår en film retteligt kan kaldes god: ”Vi kan kalde en film for udmærket, når den indgyder os en eksalteret idé om det filmiske.”

Med forbehold for Bressons egen definition af ”det filmiske” kunne hans kriterium forsøgsvist omsættes til, at man skal prise den film, der giver én en eksalteret idé om filmmediets potentiale. Man kan imidlertid også vælge at læse Bresson bogstaveligt og værdsætte den film, der udmærker sig ved sin kinematografiske egenart – altså ved at eksperimentere med selve det billedlige udtryk. Og netop det har en række film på ikonoklastisk vis gjort i kølvandet på digitaliseringen af filmmediet de sidste par år.

Imens 35mm celluloidfilm er blevet afviklet som mediets definitive indspilnings- og fremvisningsformat til fordel for harddrives og High Definition, har man set en parallel (protest)bevægelse i form af spillefilm, der helt eller delvist er optaget på antikverede, analoge videoformater som VHS og U-matic med udvaskede, støjende billeder til følge. Et anarkistisk greb, der undergraver mange populære forestillinger om forholdet imellem billedkvalitet, æstetisk nydelse og filmhistorisk udvikling. Og som altså ikke mindst, med Bressons ord, giver anledning til nogle eksalterede idéer om filmens fortsatte potentiale.

Nogle eksempler: Pablo Larrains No (2012) er en film optaget på det bedagede tv-format U-matic, men er ellers en relativt konventionel arthouse-film med en kendis i hovedrollen. Analog video har dog især haft et comeback i det eksperimenterende felt mellem indie, undergrund og avantgarde. Harmony Korines Trash Humpers (2009) blev optaget og klippet direkte på et VHS-bånd, Andrew Bujalskis Computer Chess (2013) er optaget i udvasket sort/hvid på et antikveret Sony-videokamera, og Måns Månssons svenske meta-krimi Roland Hassel (Hassel – Privatspanarna, 2012) er ligesom No optaget på U-matic. Dertil kommer de danske kunst- og undergrundsfilm Båndet mareridt (Taped Nightmare af Iselin Toubro fra 2012) og The Bedridden Triptych (af Deniz Eroglu ligeledes fra 2012), der begge er helt eller delvist optaget på VHS og VHS-C.

Alle disse film har været vist i Danmark indenfor de sidste par år og er genstand for de følgende siders forsøg på at besvare det dobbelte spørgsmål, der trænger sig på, når man observerer brydninger i et medium, der, siden det kom til verden, har været i konstant forandring, nemlig: Hvorfor denne nye bølge? Og hvorfor lige nu?

The medium isn’t the message

Udfasningen af celluloidfilm til fordel for harddrives har været båret frem af et løfte om stadig højere billedkvalitet i en grad, hvor billedets opløsning i sig selv er blevet genstand for en euforisk begejstring grænsende til en form for HD-fetichisme. Hvis billedlig skønhed i sin romantiske definition er ’et løfte om lykke’, synes det digitale HD-billede snarere at love én ubesværet nydelse – et løfte, der gerne indfries i intenst kolorerede naturmotiver, detaljeret slow-motion og close-ups af skinnende celebrities, der har givet begrebet ’krystalbilleder’ en helt ny betydning. Man fristes til at foreslå, at 1980’ernes Cinéma du look, der netop var båret af glitret overfladeæstetik, kun var et forspil. Først nu er post-modernismen endelig slået igennem i filmen efter at have udspillet sin rolle i alle andre sammenhænge.

Man fristes ligeledes til at afvise HD-billedets naturlige tilbøjelighed til en form for perceptuel hedonisme – en narcissistisk og dekadent overtydelighed, der nærmer sig det pornografiske – og i stedet med den franske filmtænker André Bazin besynge det ’ægte’, analoge filmbilledes indeksikalske troværdighed, dets fysiske relation til virkeligheden; den sande film, hvor selve den kemiske kærlighedsakt imellem lysfotoner og filmrullens emulsion er en grundbetingelse for cinematisk såvel som moralsk værdi.

Men man må besinde sig. For nu at blive i den filosofiske jargon fra Bazins tid, så har de levende billeder (digitale som analoge) ikke i sig selv nogen essens forud for deres blotte eksistens og ingen naturlige tilbøjeligheder i retning af det ene frem for det andet.

Om noget er det snarere bekymrende, hvordan digitaliseringen af filmmediet nærmest har relanceret den bazinianske forestilling om det analoge filmbillede som uangribelig garant for en ’objektiv’, fotografisk autenticitet – en puritansk reaktion på de digitale billeders fremkomst, der tilsidesætter filmmediets kompleksitet, som filmteorien i et halvt århundrede har arbejdet med at begribe. Digitaliseringen har ikke desto mindre, ligesom alle andre små og store teknologiske revolutioner i filmens historie, sat sit aftryk ikke blot på, hvordan filmene lyder og ser ud, men også på publikums forventninger til, hvad der er værd at (betale for at) se på. Og her kan man argumentere for, at HD således ikke blot er blevet dominerende som optageformat, men også som stil – en kinematografisk trend, om man vil, i retning af ’rene’ billeder, hvis detaljerigdom foregiver en høj production value.

Hvad der følger her, er for så vidt ikke en afvisning af HD-formatet, der ligesom alle andre fotografiske formater besidder sine egne ekspressive kvaliteter. Der er heller ikke tale om en forsvarstale for celluloidfilm eller om en ontologisk differentiering imellem analoge og digitale billeder. I visse tilfælde viser film, der ellers umiddelbart udviser alle HD-formatets excessive kvaliteter, sig at være optaget på 35mm-film (eksempelvis Harmony Korines Spring Breakers (2012)). Spørgsmålet, om man overhovedet kan ’se forskel’ er også underordnet i denne sammenhæng.

Formålet med de følgende sider er nemlig i stedet at se nærmere på en række film fra de seneste par år, som er optaget på antikveret video. Og igen kan man starte med at spørge sig selv: Hvorfor denne nye video-bølge? Og hvorfor netop nu?

Er brugen af analog video et symptom på en retro-nostalgi, der morbidt genskaber den nære fortids ’look’ for at tilfredsstille tilskuerens behov for at forlige sig med tidens uafvendelige gang? Er der tale om en ’instagrammificering’ af filmkunsten? Om en ironisk blasé eller om autentisk dedikation?